How the Coronavirus Outbreak Upended the Meat Supply Chain

June 22, 2020

Written By Adam Buckallew

The protein production pipeline is backed up and the repercussions are already being felt by farmers and consumers.

Grocery store meat cases are emptier, some fast food restaurants are unable to offer standard menu items, and food prices are up across the board. In April, the overall price of meats, poultry, fish and eggs increased by 4.3%, with egg prices alone jumping 16.1%.

On the farms of livestock producers, the situation is grimmer.

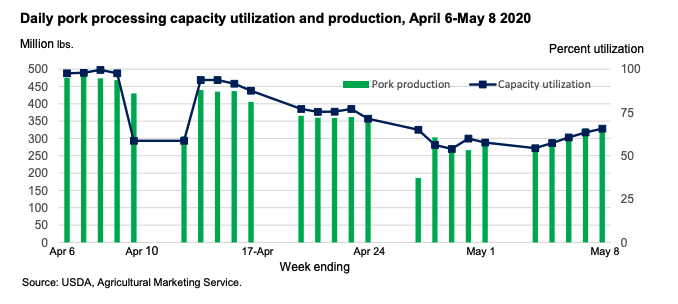

When a rash of COVID-19 outbreaks forced nearly two dozen slaughterhouses to close in April, it sent a historic shockwave through the meat supply chain. Approximately 40 percent of pork and beef processing capacity had been lost by the end of April, preventing hundreds of thousands of market-ready livestock from being sent for processing.

Howard “A.V.” Roth, a pork producer from Wauzeka, Wisc., and president of the National Pork Producers Council, said in a news release that he and his fellow farmers are facing “a dire situation” and that they are “taking on water fast.” Roth said immediate aid is necessary or “a lot of hog farms will go under.”

Bottlenecks and Backlogs

Brent Heid, who raises weanling pigs at Lone Tree Farms in Harrisonville, Mo., said pork producers operate under a “just-in-time” model. The tight schedule, which begins when a sow becomes pregnant and ends when her pigs are sent to the packing plant approximately 300 days later, relies on a consistent and well-orchestrated process that has been upended by the coronavirus pandemic.

Typically, about 500,000 hogs are processed in the United States daily, but the April closures and slowdowns at packing plants meant up to 200,000 hogs per day were being stranded on farms with nowhere to be shipped.

Under normal market conditions, farmers operate under the assumption that they will be able to send off their mature hogs to slaughter so that they will have room to raise younger pigs, said Jayson Lusk, an agricultural economist at Purdue University.

“If the finished pigs, who weigh about 280 pounds, are unable to head to the packing plant, there is no room in the barn to receive the new batch of pigs from the nursery,” Lusk explained. “If the nursery isn’t vacated, there is no room for the piglets. All the while, new piglets are being born with nowhere to go. Thus, the closure of packing plants leaves farmers with no good options.”

Heid, who raises more than 100,000 weaned pigs a year, says he has yet to run into any issues finding buyers for his piglets, but he knows “there’s a big backlog” of market-ready hogs that farmers are stuck holding.

While pigs can be fed more fiber and less fat to slow their growth, the window of time to harvest mature hogs is narrow. Once pigs reach six months of age, they can quickly grow too large for processing. Some meat plants will not accept hogs weighing more than 300 pounds. In contrast, cattlemen have more flexibility as most cattle typically mature at 18 to 22 months of age and their growth can be delayed by switching them from grain feed to a pasture-based diet.

A May report from agricultural lender CoBank said the bottleneck in the U.S. meat and livestock supply chain has plunged “margins for cattle and hog farmers” to “multi-year lows” as the supply of livestock has far outpaced processors’ capacity to purchase them.

“As meat plants have closed, farmers are left with few options for their livestock, requiring herds to be culled,” said Will Sawyer, lead animal protein economist with CoBank, who authored the report. He noted livestock producers are “trying to stretch the supply chain like a rubber band” and “expand the life cycle of their animals as much as possible” as they wait for improvement in the meat industry’s processing capacity.

Getting Back on Track

Meatpacking plants, where many employees often work elbow-to-elbow while cutting deboning and trimming meat, have become coronavirus hot spots. So far, at least 30 meat plant workers and four U.S. Department of Agriculture food safety inspectors have died of COVID-19 complications and more than 10,000 across the country have been infected or exposed, according to the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union.

At least 30 plants have suspended operations since the outbreak began in March, and many more have reduced operations as meat processors have scrambled to institute new safety measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and keep protein supplies moving. Metal and plexiglass partitions have been installed at some plants, plants have introduced mandatory temperature checks for employees before they can begin their shifts, personal protective equipment has been provided to workers, and companies have increased the frequency of cleaning and sanitation.

As the meat industry grappled with the fallout of plant closures, John Tyson, chairman of Tyson Foods, warned the “the food supply chain is breaking” in a full-page newspaper ad that ran in some of the nation’s largest newspapers on April 26.

“We have and expect to continue to face slowdowns and temporary idling of production facilities from team member shortages or choices we make to ensure operational safety,” Tyson said.

Within three days of the Tyson advertisement, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that gave Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue the power to invoke the Defense Production Act to force meat companies to keep their plants open.

Perdue issued a pair of letters to state governors and leaders in the meatpacking industry that called for following the guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration “with respect to any current or proposed actions that may lead to a reduction in the nation’s meat and poultry food supply.”

In his letter to the meat companies, Perdue said plants “contemplating reductions of operations or recently closed” that have yet to establish a clear timeline for resuming operations should “submit written documentation of their operations and health and safety protocol developed based on the CDC/OSHA guidance to USDA.”

During a meeting at the White House on May 6, Perdue expressed confidence that the meatpacking closures and the meat shortages that had prompted supermarkets to put limits on fresh meat purchases may soon be coming to an end.

“I think we’ve turned the corner,” Perdue said in an Oval Office meeting that included President Trump, Vice President Mike Pence and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds. “We’ll see them coming back online. Obviously, because of some infected employees, they won’t be full force for a while, but we think the stores will be — you’ll see more variety and more meat cases fully supplied.”

Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig – whose state raises more than one-third of the nation’s pigs – said the pressure to keep plants running has helped farmers in his state.

“We have less than 5,000 head of market-ready hogs that have been euthanized and disposed of in the state of Iowa,” Naig said in an interview with Harvest Public Media on May 18. He cautioned that number could still go up but said the reopened plants may have helped pork producers avoid worst-case scenarios.

During a May 14 webinar, CoBank’s Sawyer said while April was perhaps “one of the worst months for animal producers ever,” the situation at meat processing plants has improved. He pointed to overall capacity utilization at packing plants rebounding by 15 percent to around 70 percent, but noted those rates are still well below the 95 percent capacity the industry was operating at in late March.

Sawyer said while President Trump’s executive order to reopen the closed meat plants appears to have stemmed the tide of additional plant closures and paved the way for closed plants to reopen, attracting workers to fill the thousands of vacant positions at meat plants across the country will continue to be an issue.

In a May market outlook, USDA economists cited “continued workforce infections and in-plant social distancing measures installed to reduce virus contagion risk” as constraints that would slow the flow of meat processing for the remainder of the year.

“The United States is facing an unprecedented situation and it will take a while to return to what life was like before COVID-19,” Sawyer said.