Goodbye, El Niño; Hello, La Niña?

April 24, 2016

Written By Adam Buckallew

As one of the strongest El Niño weather cycles in the last 65 years begins to weaken, the question on the minds of many is what will come next? Will the Midwest have a return to weather more in line with a typical year, or will a new weather phenomenon emerge with the potential to affect temperatures and precipitation totals?

The answers to those questions will largely depend on how long the El Niño phenomenon persists and whether a La Niña develops afterward, says Tony Lupo, an atmospheric science professor at the University of Missouri.

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of what is known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. The ENSO cycle is a scientific term that describes the fluctuations in temperature between the ocean and atmosphere. When oceanic waters in the Pacific are warmer than normal, El Niño occurs. By contrast, La Niña is characterized by cooling temperatures in the Pacific Ocean.

Lupo says he expects the current El Niño conditions to ride out the spring until May. What happens next will determine how the summer weather plays out.

“El Niño and its transitions are the 800-pound gorilla when it comes to our weather,” says Lupo. “El Niño and La Niña impact our winter seasons, while the transition from one to the other dominates summer.”

According to Al Dutcher, a climatologist at the University of Nebraska, four out of every five El Niño events since 1950 have been followed by a La Niña event and that transition occurs within a 12-month period.

“The one out of every five that doesn’t still goes to the cool side in the Pacific Ocean,” Dutcher says. “It just doesn’t meet the quantifications of La Niña conditions as defined by the Climate Predication Center. So we still see some of the same patterns with those weaker events that don’t quantify as La Niña, but they can still have an impact on the upper atmosphere.”

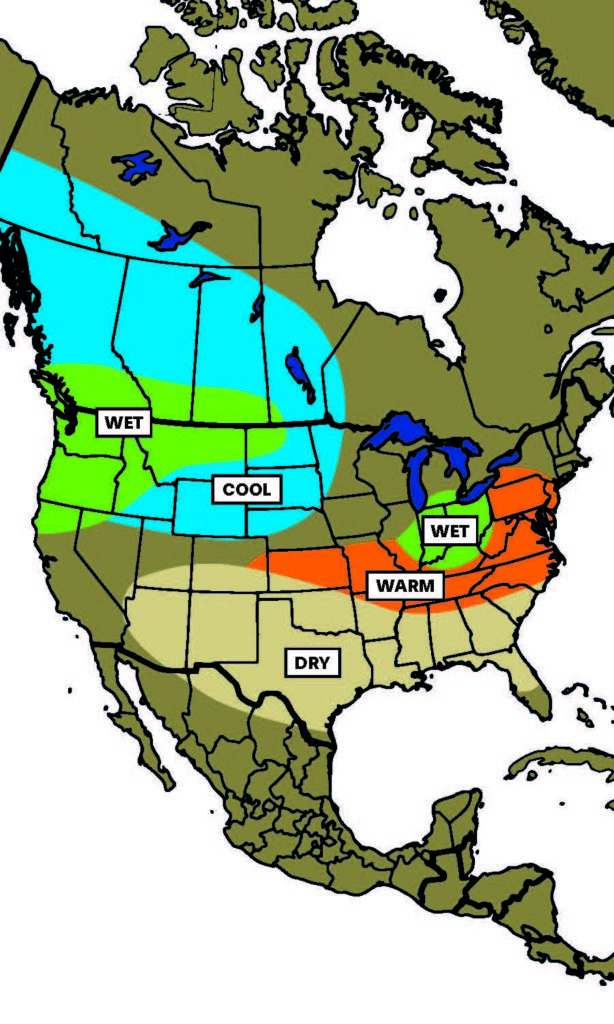

Transitions to La Niña often bring the Midwest hot summers and irregular rainfall, and that fits with Lupo’s prediction for the upcoming summer.

“Spring should be cooler with normal precipitation,” Lupo says. “This summer could be warmer and drier than normal.”

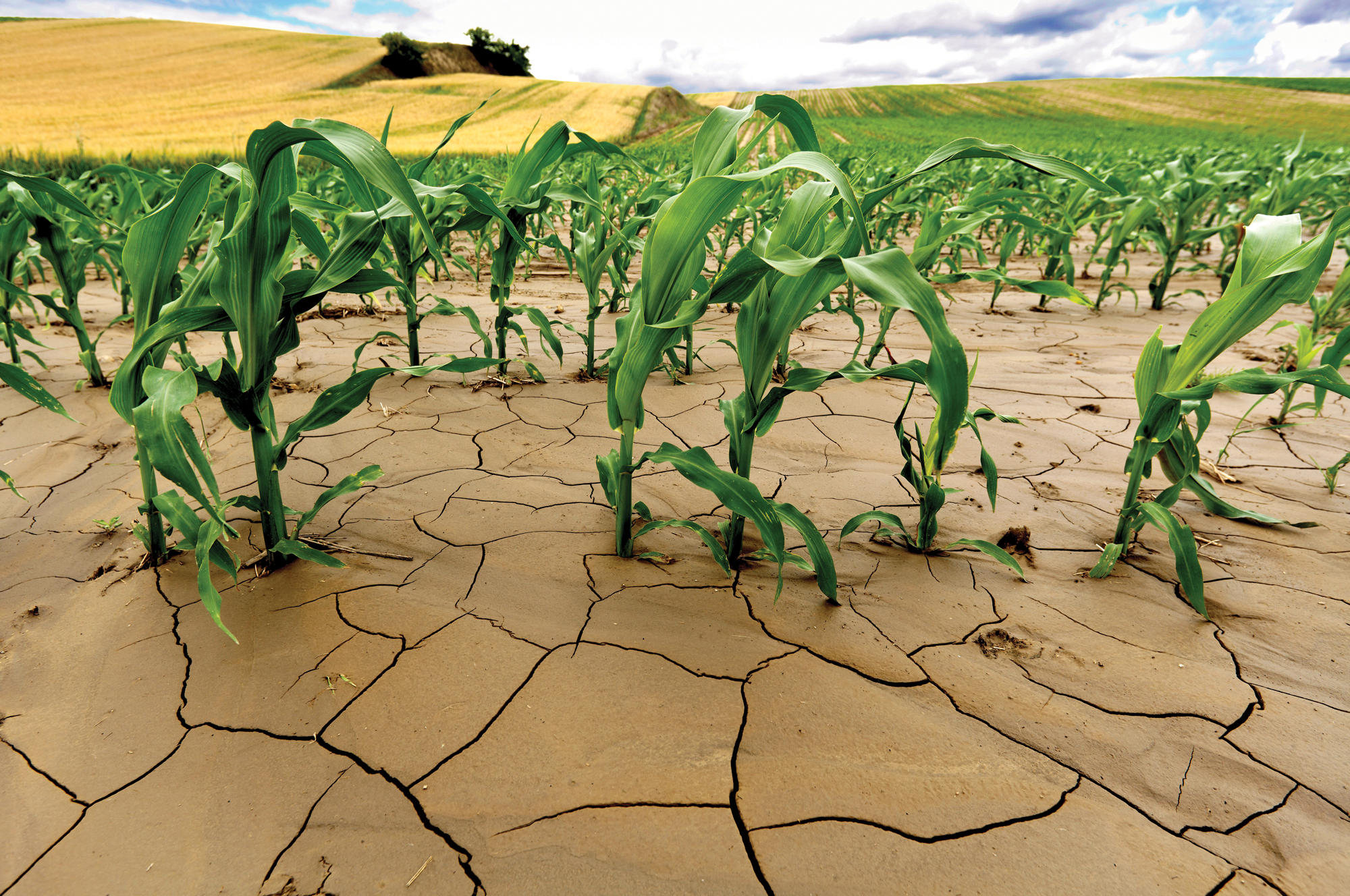

A developing La Niña could mean bad news for farmers. In 2014, Lupo and one of his students, Jessica Donovan, analyzed harvest records for corn, soybean and wheat back to 1920. Controlling for the effects of technology on yields, Donovan found a definite correlation between El Niño/La Niña and Missouri’s corn and soybean yields.

“We’re finding that when it’s transitioning into El Niño years, the corn yields are higher,” Donovan said. “Then when it’s transitioning into La Niña, the corn crops don’t have as high yields.”

The study found the same trend to be true in soybeans, though the effect was not as strong as it was with corn.